Retrogamer: Fool Me Once

Michael B. Tager

The typewriter makes a simple request: identify yourself. If your name is new, it wants to be reassured that yes, you are indeed a new officer of Interpol. Y/N? Press enter. And welcome to the force, rook.

Ivan the Terrible’s crown has been stolen. Suspect is a male. Track that thief down and bring the jewels back, rook. And don’t forget to get a warrant, or that crook is going back out there, to steal more priceless, name brand artifacts. Do it by the book. Listen to the anonymous, faceless fruit sellers and merchants; they’ll identify the criminals by oddly specific scars and vehicle preference. It’s how crimes are solved.

I saw the man, says the hot dog vendor at the New York airport, where you’re questioning potential witnesses. He has red hair, and he hates dangerous sports, the man says. And he’s going to Timbuktu. You check the flights: one leaves right now for Bamako.

Bamako. You’d never heard of it until now. You’ll be there soon.

Before you leave, you stop in at Interpol HQ. You eliminate suspects one by one. You’ve known it wasn’t a woman from the jump. Now you know he has red hair. And you know he hates dangerous sports. There’s a list of possible activities of Sandiego’s gang. You don’t have time to backtrack, your week is almost up. You guess. You type dancing and all suspects are eliminated. You think. You type swimming. A name comes up: Scar. You hope you’re right.

You land in Bamako after midnight and despite everything you’ve done, you’re forced to sleep. The venue is irrelevant. You’re out for 8 hours. When you wake, you head to the embassy and barely dodge a knife! And there the suspect goes. You and your fellows chase with billy clubs drawn.

You capture Scar and sigh. He had the crown. You got lucky, rook, you tell yourself.

The chief calls you into her office. You’ve earned a promotion, sleuth, she says, for your capture of Scar. You hope to tattoo your promotion and your pride on your heart. Wipe that grin off your stupid face, another case came in. Don’t fuck it up, she says, iron in her breath, but she winks as you close the door.

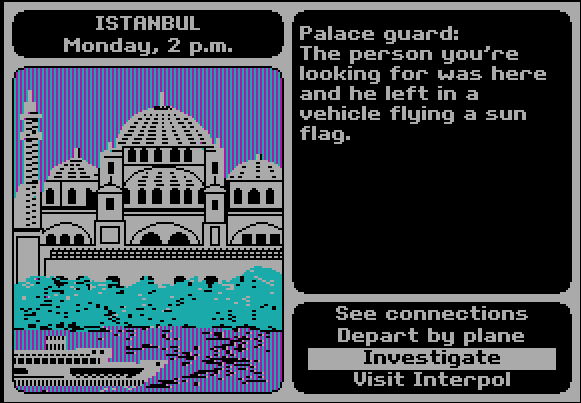

You study the file. A woman stole an emerald from Istanbul. Maybe it’s Carmen, you whisper into the wind, ready to take the case. In a few more cases, maybe you’ll be promoted. Unless you fail? You shake off the doubt; off into the night you go. You’ll start in Istanbul, see where the road leads.

Soon, you come to at a dead end; where the hell is Lake Ladoga? How will you ever find out?

You have a lot more cases to go before you are respected, before you are the man; 14 is the number that pops into your head, unbidden. You’re ready. You open your research materials and your newly-tattooed heart. It’s time to work.

Last week, my friend Andrew sent me a link for a site full of old games. They were cranky, rusty programs, designed for a populace and time that no longer exists. But they exert an odd kind of exigency and appeal and they remind me of a time when I could have well-used their old school charm. Especially that brand of gaming that’s often derisively labeled “edutainment.” Games like Oregon Trail, Sim City and, of course, Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?.

In 2004, I worked at a Boys and Girls Club in Denver. Most of my time was spent in the game room playing Connect Four and foosball with the middle school crowd, occasionally helping with homework and quietly avoiding giving any bad habits to impressionable youth (i.e. my smoking was done before and after work). It was a simple time.

That particular Boys and Girls Club was a nicer-than-normal affair and, besides the area that I haunted, it contained a fancy education room, a deluxe art space and a brand new computer room. The computer room especially was fancy, with glass windows, 30 or so IBMs and a constant patrol of kids searching the internet for whatever they weren’t supposed to be looking at. Some did homework, as it was ostensibly intended for, but mostly, they played games: spades, Half Life, off-brand Flash games. There was a strict time limit on each computer and the kids cycled in and out, in and out. It was probably the most popular room in a very-full club. Except for one hour a day, when it became a ghost town.

That hour was the only time when me and my co-workers would set foot in there to do more than hall monitor. That hour? Educational games hour.

I love educational games. I love being fooled into learning. It’s like, fool me once, please, fool me again.

Back then, I mostly played geography games like The U.S.: 50 States or even this Countries of the World quiz. Sometimes I thought about playing classic games that were more game-like, and maybe I even did. It’s been 12 years, who knows. But what I remember was trying to fill in all the countries of Africa and being tripped up by Mali and Malawi. Or forgetting that Guyana is in South America and not next to Burkina Faso, where it really doesn’t belong. And let’s not get started on my confusion with the placement of Laos and Cambodia. I spent hours remedying my shameful ignorance and the kids at the Boys and Girls Club could not have given less of a shit.

I shouldn’t have been surprised that the kids at the Boys and Girls Club, even the ones who latched onto me as a mentor/older brother and were constantly asking me for advice and opinions (for some reason I was quite popular with the 8-10 year-old boys and 11-12 year-old girls) totally brushed me off when I tried to interest them in the geography games that I was obsessed with. “Oh neat,” they’d say, and wander off to buy some Cheetos or play basketball with the older kids.

After a series uncomprehending failure, I eventually thought back to when I was a kid and how my interest in geography was only in finding funny countries, like Djibouti or Georgia-not-the-state. Why did I think that these kids would be any different? There were some nerdy kids there, of course, and I played chess with them, but even they weren’t interested. While I never gave up entirely, I lessened my efforts and soon enough, my time at the Boys and Girls Club was over and I never quite got any kid interested in any edutational games. Those were, incidentally, the only games I played in the entirety year of 2004 (besides Kingdom Hearts).

Looking back, I wonder if my modus operandi wasn’t flawed from the beginning. Those fill-in-the-blank games are basically just quizzes and the crappier ones are clickbait, designed to fool people into thinking they’re harder than they are. They aren’t really games so much as devices to help/irritate those that already want to know the information. They aren’t designed to engage or entertain. In fact, their quiz nature will likely turn off just as many as they’ll successfully engage. The only people who dig quizzes are those that test well and get off on that—I was never a good student, but slap a quiz or a test in front of me and I was likely going to score well.

Now, there are plenty of actual games that aren’t just glorified memorization schemes. The difference, of course, is that a game has a hook, a plot, a mechanic, levels and, most importantly, design. Sometimes the design is simple, sometimes not so simple. Older games are often text based, mini-stories with minimal input from the gamer. The illusion of playing is had (look at the bright colors, the humor!), but it’s a well-engineered facade. Something else is going on.

When the game is educational, the design is paramount because if there’s one thing children (which educational games are designed for) hate, it’s being forcibly educated. To teach a kid through gaming, the kid has to be, for lack of a better word, tricked. And once they see through the trick (which they eventually will), it has to be good enough to keep them playing.

I wonder if I would have had more success with my pupils if I had tried to use games that were actual games. I don’t know why I didn’t. Maybe I didn’t think of it. Maybe I didn’t have access to it. I mean, this was over ten years ago. That’s a long time when it comes to access to games. Steam had been recently invented, but I sure as hell didn’t know about it. Cell phones were primitive enough that game-playing was limited to Snake, and I didn’t even own a cell phone, for that matter; I went with what was available.

When I “discovered” Archive.org and its plethora of old school MS-DOS games, I didn’t immediately think about my time at the Boys and Girls Club. No, I mostly just thought about playing some Oregon Trail, which I did, and loved. It was only after I played that for a couple hours and relived my middle school euphoria that I noticed Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?. I’d never played Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?, of course. I’d somehow missed it.

I’m not sure how I didn’t play Carmen. It came out in 1985 and had something like ten re-releases and sequels. There was a cartoon that I was vaguely aware of, and a game show. I was alive back then and nerdy and into video games. I knew of Carmen’s existence. But I never, ever played it.

When I explain to those younger than me how I missed so many pop culture references that are ubiquitous to them, there’s one fact that often blows their mind: with the exception of two or three years of summer camp, I didn’t touch a computer with regularity until the mid-90s (and didn’t own a cell phone until ’03). I was born in 1980, the last year of Generation X. I have more in common generationally with those born in the 70s than those in the 90s. That computers are such a fact of life now still sometimes surprises me. My first instinct, even now, is to go to an encyclopedia or dictionary for reference.

Computers just weren’t commonplace in my formative years. And while I had near-constant access to video game consoles and arcades, computer games were not on my radar until 1995, when I took a computer class. In high school. I didn’t own a computer of my own until I was 18 and I had to dip into long-term savings to pay for it. It just wasn’t a thing.

Even when I could have played Carmen Sandiego, I somehow skipped over it. Unlike Oregon Trail, it wasn’t on those summer camp computers, and, unlike Sim City 2000, it wasn’t a part of the curriculum in Tech Ed class, circa 1994. Where else would I have played it? And by the time I got my own computer, well, I wasn’t going to of out of my way to play Carmen Sandiego. It’s like when Leigh was shocked I had never seen The Lion King. I was 14 when that movie came out and I had no younger siblings. What insecure teenaged boy is going to bother to check that out, if not forced?

These weird generational gaps happen all the time. Leigh and I are only three years apart in age, but our pop culture radar is entirely different. She’s never seen an episode of The Smurfs whereas I watched that shit every day. Alternatively, the music that she cut her teeth on was all released in the late 90s and 00s, a time where I was far, far too busy to pay attention: I was in college and then in the real world. I was busy. My parents were aghast when I told them I’d never seen M.A.S.H., but I was five when it went off the air. My nephew has no idea what I Love Lucy or The Brady Bunch or Soul Train is like; I watched all of those on Nick at Nite, a channel that I’m pretty sure stopped existing decades ago.

And this is why I never stopped to consider Carmen Sandiego when I was trying to get kids interested in geography. It was this little cultural niche that people of a certain age are hyper-familiar with and everyone else missed entirely. Carmen Sandiego is basically Nightrider: slight, uninteresting, thin. Or so I assumed.

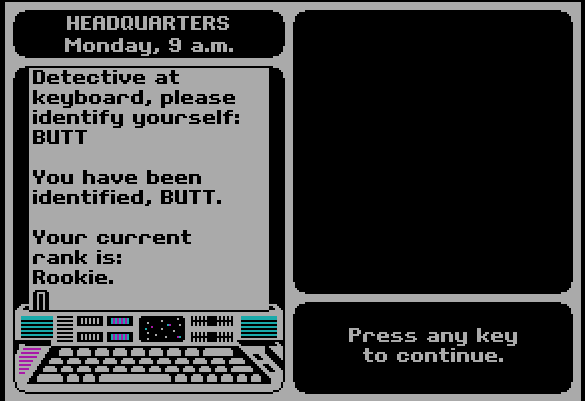

Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? is, for those unfamiliar, a simplistic MD-DOS game. There’s no reflexes involved or real choices made and all choices are made by typing Y/N, using the arrow keys and pressing enter. The player character (in this case, BUTT) is a rookie detective for Interpol, given the task of solving jewelry heists around the world; because I was channeling the early 90s, I named my avatar BUTT. The heists seem to be all randomized in the Clue style: there’s a set of 10 or so possible members of the gang, 30 countries and 20-ish items that could be stolen. When each case is booted, an algorithm decides on the combination. It could be Ihor Ihorovitch who stole the crown jewels and is chilling in Buenos Aires. But it could also be Dazzle Annie or Lady Agatha stealing a pet cat and hiding out in Paris.

Once the player starts, they are given clues to track down the case and given one week to solve it. In every country visited, there are three locations for clues and then it’s off to a different country. Go to the right country and glimpse henchmen and find more clues. Go to the wrong country and bupkus.

One clue might be that the criminal changed all their money to dinars. What country uses dinars? If the player knows the answer is Iraq, they’re off for the next clue with the endorphin rush that accompanies knowledge mastery. Suddenly, dinars are a part of their lexicon, imprinted in their memory banks by chemicals and association. Because that’s how education and learning works. Successfully learning something new creates a spark in the brain and pleasureable neurotransmitters flood the brain, creating new channels and memories. Some people get addicted to learning. And some people are addicted to video games (other, different neurotransmitters). That’s the entire point of the edutainment industry: learning through fun (and trickery) and marrying two kinds of addiction and linking them inextricably.

But what if the player doesn’t know what the hell a dinar is? Well, that’s OK, because that’s the next part of the game. Teaching how to find the answer.

I wonder how schools teach research nowadays. My students seem to only use Wikipedia and Google and have no concept of critical thinking. If the answer doesn’t turn up on those two avenues, they’re utterly poleaxed. Of course, the flipside is that a large percentage of the time, those two avenues do have the answer. so why bother learning another method? It’s an interesting problem that didn’t happen back in 1985 (or really until the mid-late ‘90s when search engines became popularized).

I can fully envision the scenario: a teacher announces it’s time for Carmen and assigns kids to a computer. Then the teacher hands out atlases, encyclopedias, dictionaries. Maybe one kid is assigned to click and type Y/N, maybe another is assigned the dictionary. There might have only been a few computers to a classroom, so assigning multiple kids to one project made sense. Then the game began and, working as a team, they came up with answers. Where are the Ural Mountains? If they didn’t play Risk, they’d have to find out from an atlas that it was near Russia. What about gauchos? I mean, what are they? If they didn’t have any knowledge of etymology, they might not recognize the Spanish root. But if they did, they still couldn’t narrow it between Buenos Aires or Lima. There would be more clues for to tell them apart.

The kids might have thought they were simply playing—and they were—but they were suddenly knowing useful facts. Their worlds would have been expanding, perhaps imperceptibly. And their skills with research, organization, geography, even the law (getting a warrant from details garnered is also a requirement) would be blooming, without their knowledge.

When I booted it up this past month, I knew I was playing in a different sphere. The game was not designed for a grown man with (possibly) greater-than-average knowledge. I’d been to Europe and Mexico and Costa Rica and Japan; I played Risk; I read widely. The vast, vast majority of the game was simple, but even so, I still had to Google flags and terms I was unfamiliar with. I had no idea that the Sri Lankan flag was that of a golden lion; I might have thought Mount Karthala was somewhere in India, not Comoros. And I loved learning these facts. I love remembering these facts. Will they be useful? Maybe. That’s not the point.

From start to finish, it probably took me two or three hours to beat Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?. I was doing other things, like cooking dinner and watching TV with Leigh. I lost two or three cases by not paying enough attention or by thinking I knew that, of course Egypt doesn’t use pounds as their currency (spoiler: Egypt does). I kind of enjoyed losing. It forced me to pay attention and tap into the level of awareness that forges memories. And I loved that; I dimly tapped into that kid who played Oregon Trail and Sim City and knew he was being edutained and didn’t care. When I captured Carmen Sandiego on the final level of the game, it felt like a legitimate accomplishment. I might have been 20 years late, but I know exactly where in the world the fuck Carmen Sandiego is.

See, all these years later, I’m still being edutained.

Those kids at the Boys and Girls Club maybe could have benefited from a little Carmen Sandiego, but they’ll be fine that they missed it. There’s undoubtedly some edutainment game that I’m wholly unfamiliar with that they absorbed in its entirety. Or like me, they’re dimly aware of it and will check it out when they grow up. And guess what? Those kids are now in their twenties and they’re probably all fine. And they’ll come across Carmen Sandiego on their own or they’ll introduce their own edutainment games to the kids they come across. It’s all a culture circle.

Me? I’m just happy I had a brief dalliance filled with a memory that I missed out on the first time around. And, shit, I learned that Moroni isn’t just a silly name on a map. About time, rook.