This Is (not) Your Beautiful House

Michael B. Tager

(Before reading, click to play One Chance. It’s simple and short. Spoilers abound.)

On the first day, Dr. John Pilgrim arrives at his office. His colleague says, blow off work, come party. All seems well in the world—he’s just cured cancer after all—so he decides that ditching out and embracing irresponsibility, for once, is justified.

You’ve just gotten home from New Hampshire, your second year of AmeriCorps. You have no money and are working a series of nothing jobs. Your mother calls you one day and says, “My secretary just quit. Do you want to come and temp for me for a couple weeks?” You aren’t doing anything you care about, so of course you say yes.

There’s a saying: “this is the first day of the rest of your life.” The past is over, and every day when we wake, we’re reborn. The future is unwritten, and, with the right choices, we can create the perfect world. The rest of our life stretches before us, endless, and we can tread in any direction, do anything, make the world turn with the right lever.

Monday: I wrote some words in my novel and went to FedEx so I could construct a zine. I walked through Johns Hopkins’s campus. Brian and I discussed video games over Google-chat There were flowers and pretty co-eds. I laughed with a worker at FedEx. At one point during the day, I sent emails to my father-in-law. At the end of the night, I watched Aladdin with Leigh instead of Rear Window.

On the second day, Dr. John Pilgrim discovers that the cure he’s made is actually going to destroy the world; it attacks everything, not just cancer. When he arrives at work, he heads up to the roof, ostensibly for fresh air. Outside, in the bright light of day, his despondent colleague commits suicide while John watches, horrified.

You are at a meeting with your mother/boss and two women you’ve never met. The new women seem nice and when you shake hands, you make an offhand joke that you can’t remember minutes later. The women laugh. Later, when you have to take a call, you excuse yourself politely, professionally, firmly, and leave the room. When you return, the woman with the short hair says, “So, you’re just a temp? We have an opening. Would you like it?” and you say, sure, sounds great.

The flipside of the “rest of your life” argument is, of course, that every day is the first day of the end of your life. This is just as true of a proposition. At some point in the future, we will die. Everyone we know will die. Our children and their children and their children’s children will die. And the sun that burns in the sky will also, one day, die.

Tuesday: I had my reading series. I invited people from work, but not many, because I’ve made the mistake of getting too close to colleagues. The reading was successful, but I had to shake many hands and tell stories to strangers. There were too many micro-decisions to make, too many ramifications to process from those decisions. At the end of the reading, I went to the bar for a little while instead of going home. One of my friends mildly hurts my feelings, feelings that wouldn’t have been hurt if I’d just gone home.

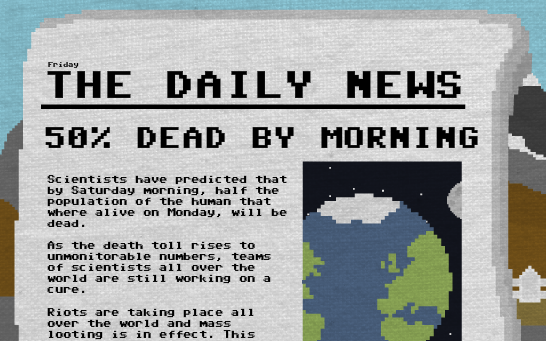

On the third day, Dr. John Pilgrim’s wife asks him to stay home. He feels responsibility, however, a guilt that cannot be assuaged. Despite his wife’s requests, he heads to work. The newspaper’s report is not optimistic.

Your mother calls you at a poker game. She asks if you’ve heard about the Obama rebate for those in the market to buy a house. “Of course,” you say, wondering if you should bet the triple threes you have or represent the flush-draw. Your mother asks if you’re going to buy a house, now that you have a full-time job and are making money. “I haven’t thought about it,” you say, as you decide to slow-play the trips. Your mother tells you that it’s a good time to invest in land. “I’ll think about it,” you say as you lose to the river rat who caught the flush.

Of course, all this “first day” noise is just abstract talk. What if today was literally the start of the end? What if there were only a handful of days left? Wouldn’t every choice have added meaning? That’s the point that the flash game One Chance is making. It’s not about winning and losing, it’s about making difficult decisions and living—and dying—with the results of those choices.

Wednesday: Leigh and I went to a financial planner and he asked us difficult questions to which we didn’t have answers. He also showed us art and I chose to take a picture of one of them because I thought it was lovely. Later in the day, Leigh and I went to my parents to discuss money. No decisions were made. When we got home, we watched Rear Window, finally, so we can return the DVD to Netflix. I was proud of myself for finally watching such a classic (I’ve been on a classics kick). Leigh then went to sleep and I played Rimworld until 4 a.m. It was a bad decision. I knew was bad while I was making it.

On the fourth day, Dr. John Pilgrim’s wife is sick and he can’t find his daughter Molly. He drives through the semi-deserted streets, knowing that 50 percent of the world is supposed to die tomorrow. When he arrives, his boss tells him to go home and spend time with his family. If this is the end, that’s where I want to be.

You haven’t decided what to do about your job. You know you don’t want to be there forever—you want to be a writer—but you also know that you need a day job. You’ve finally gotten promoted after God knows how long and you have decisions to make. You suspect that you’ll be leaving soon, either the state or the city or whatever, so you decide that the pension plan isn’t for you. Instead you opt into the optional retirement plan, which is just free money. What are the odds that you’d make it twenty years to qualify for the pension?

One Chance is just like real life, except the stakes are higher, much higher. Most of us, we face decisions that have ramifications, yes, but the consequences are simply not terribly severe. We don’t live in a world where every decision is literal life and death. If we don’t fill up gas on the way home from work, we might be late the next morning. It’s a problem, but not in the macro sense. In One Chance, the fate of the world is in the player’s hands.

Thursday: I went to work. I told a colleague I hadn’t had time to read her writing, which was true, but I didn’t have to tell her. I could have waited until Friday, when I planned on reading and sending notes. When I left work, I walked home. There were two events I was invited to, but I was exhausted so I decided to skip them, with apologies. I went to Whole Foods to get dinner and while I was there, decided to buy Leigh some food presents. I watched Bojack Horseman until she came home. Bojack is about a washed-up sitcom actor who makes a series of poor decisions and wonders how he arrives at poor circumstances.

On the fifth day, Dr. John Pilgrim’s wife is dead. His joints are swollen and his muscles, weak. He drives to work, through empty streets. His office is deserted, blood-splattered from the self-inflicted gunshot wounds of his colleagues. He works.

Your girlfriend has finally moved into the house and you bring up that you want to move away, like she initially wanted to do: Boston, Portland, Tucson. “Well,” she says, “I know I said that, but now I think I want to hang around here. Didn’t you just get that promotion, anyway?” When you say nothing, she continues, “Weren’t you thinking about grad school, anyway?”

There are only major decisions in One Chance. In a way, it’s a blessing. There’s no deliberation and hand-wringing over what to order off the Denny’s menu. Instead, there are seven days between the beginning of the game and the end of the world. Within each day, there are multiple choices: skip work, spend time with family, hook up with an officemate, work. Make one decision and the next day is different. Each step causes ripples. Eventually, day seven arrives.

Friday: I went to work and sent my colleague notes on her writing. I confirmed plans for the weekend. Leigh and I spent time planning upcoming trips. Then we watched Captain America: Civil War until Leigh fell asleep. I finished watching it.

On the sixth day, Dr. John Pilgrim is sick. He knows in his heart that he has failed. He had one chance.

You get accepted into grad school and because you work for the university, you get a free ride. Of course, you discover that it’s a three-year program, not the two-year you assumed. “How did you miss that?” your girlfriend asks. You have no answer, none at all, and you feel a sting in your chest when you realize it’s an additional year before your life can change. Not that you want it to change, because you’re happy, but you wouldn’t mind an option.

There are no do-overs in One Chance. The game is designed to be played one time and one time only. Finish One Chance and refresh the page, boot it again: the game is disabled. Instead of the start screen, it’s the end graphic. Of course, there’s workarounds. But that’s not the spirit of the game. One Chance is designed to be played just one time. It’s not about winning. It’s about experiencing.

Saturday: I talked with my editor and made some decisions about my future. Then I helped Steve move a file cabinet and asked him to help me redo my kitchen. Then I hung out with Dewey and Thomas and we watched A Nightmare on Elm Street, at Brian’s suggestion, because I’d never seen it. It was pretty marvelous, another in a series of classic movies eminently worth watching. Thomas and I had time to kill, so we got a beer. Then I had a meeting that lasted until 11:30. Leigh was asleep by the time I got home, so I decided to finish Bojack.

On the seventh day, the world ends. Dr. John Pilgrim moves very slowly. Despite the futility of it all, he heads to work, anyway. He has to try, even if there’s no chance. What else is there? In the end, he closes his eyes, just to rest for a moment.

You get promoted again at work. You finish grad school and are working half-a-dozen part time jobs. You’re married. You own a home. How did you get here?

There are walkthroughs and forums where those who play One Chance can hit upon the correct combination to get the “best” ending. Their motivation might be understandable, but they’re missing the entire point. Make choices, get results, learn from errors, and celebrate victories. Isn’t that enough?

On Sunday, Leigh and I celebrated our anniversary. We were going to go to the Aquarium and then eat at Shake Shack, but we reversed the decision and ate too much to go to the Aquarium, so we went home instead and watched football.

There is no eighth day for Dr. John Pilgrim. The world is finished. It has already faded to black. There will be no rebirth.

You realize that your life has taken on a shape and a life all of its own. Your decisions are small and compound each other. Point A does not lead to Point B, but to Point A-1 and then to A-2 and from there to point, like, A-2Ω and somewhere along the line, undetected by you, there is a B, but it doesn’t seem like the B it should be, instead some mutated, unsuspected Ninja-B. C is far in the distance, hidden by clouds. You have no idea how you’re going to get there, but you aren’t unhappy or particularly, just puzzled and dumbfounded by the simplicity and complexity of life.

One Chance was reviewed because the author’s friend Brian, through many, small decisions, found it. He came across it through Kongregate, through StumbleUpon, through the internet, through a series of chances and coincidences and opening of email and websites and sent it along to his friend. It’s an indie game during a time where indie games have never been so played. It’s a buried gem that feels criminally underplayed. It’s simple and quiet in a time when video games are complicated and loud. It’s contemplative. It’s an experience.

Monday: I decide to try to write about One Chance. It’s a minimalist game with retro graphics, no real gameplay to speak of. It’s a game about cause and effect, about affect, about how making decisions wreaks havoc on everyone. How do I possibly explain how the decision feels to those who haven’t played it? It takes me all day to come up with any kind of solution, even if it’s a non-linear, meta-essay with too much personal narrative and disjointed structure. It might not work, but it’s the only way I can think of to accurately express how the simple act of playing a game has touched me.