Retrogamer: Passive Participation

Michael B. Tager

Twitch.tv is a weird phenomenon. It’s an entire medium devoted to watching others play video games. The viewers are likely not playing along, like a video game version of Bob Ross’s Joy of Painting, but are instead watching (like I do with Bob Ross). The difference is that it’s not watching the creation of art by a soothing hippy, it’s instead watching some random human play a game created by an entirely separate third party. It’s another step of removal from actual activity; instead of doing something (like life), or at least playing a simulacrum of life (like video games), it’s spectation. A box within a box within a box.

I don’t get it. Or, to put it another way, I totally get it.

The animated mini-series Castlevania debuted on Netflix on July 7. My friend Brian posted effusive, over-the-top praise on Facebook the day after it came out and, buoyed by his fanboyism (and rave reviews), I gave it a try the next day. I like anime, I like Castlevania, I had just finished rewatching the 5th season of Friends. Why not give it a try?

A few hours later, I was finished. The animated Castlevania was…fine. Good in its way. While I prefer anime with multiple layers of text and meaning, a la Cowboy Bebop and Neon Genesis Evangelion, I also appreciate a good slash-fest for what it is. And Castlevania was a good ol’ slash-fest, heavy on action and oration. It reminded me of Ninja Scroll in a lot of ways, if Ninja Scroll was based on the Castlevania video game franchise that started in 1986 with Castlevania and continues through today, with 2014’s Lord of Shadows 2 the most recent iteration.

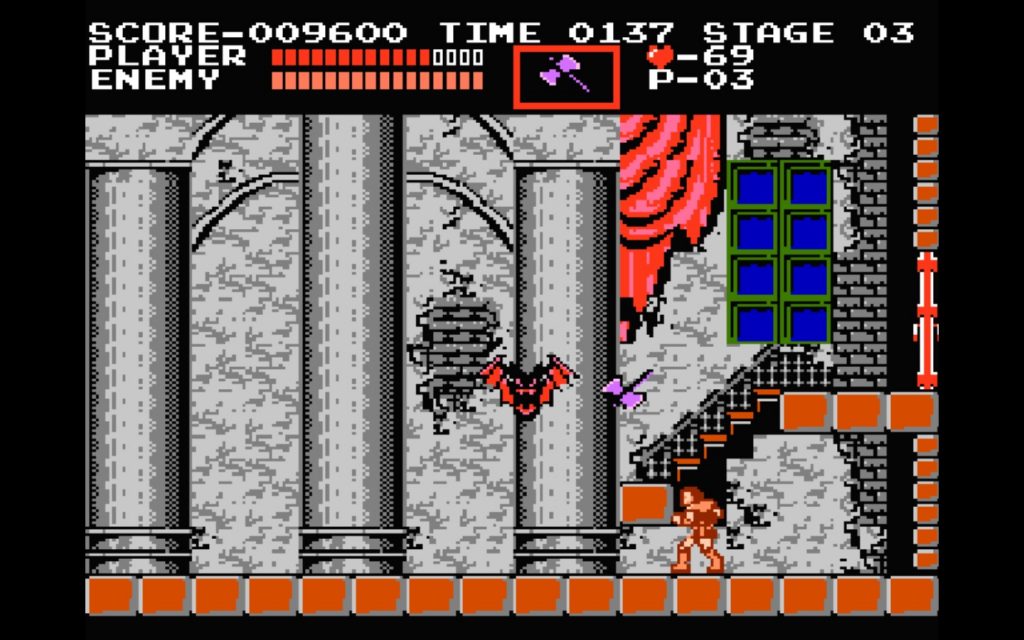

The Netflix show was a relatively faithful adaptation of the 3rd game in the series, Castlevania III: Dracula’s Curse on the Nintendo. The game’s plot goes something like this: Dracula has arisen and one of the Belmont clan must stop him, as the Belmonts are sworn/destined to do (there’s a lot of continuity I’m not going to bother to address). Along the way, Trevor Belmont encounters 3 possible companions: the witch Sypha, the half-vampire Alucard, and the thief Grant. It’s a cool game and plays like the original Castlevania, a difficult, gothic side-scroller.

The animated series hits a lot of the right notes. Trevor is the star, as he should be—nearly every Castlevania stars a Belmont—and both Sypha and Alucard are introduced in near-canonical ways: Sypha casts spells and Alucard is a badass. And while the thief Grant was excised—likely to simplify plot—from the series, it’s already been approved for a 2nd season, so maybe we’ll be seeing him regardless. The four episodes serve mostly as introduction: a gathering of evil, backstory (lifted from PlayStation’s Symphony of the Night), the coalition fighters meeting one another and then, finally, the entry to Dracula’s fortress, the titular Castlevania, filled with Rube Goldberg machines, moving platforms and many, many flights of stairs.

Watching Castlevania was fun. I knew each step as it approached, but seeing the snap of Trevor’s implausibly long whip, ice missiles flying from Sypha’s hands, the smooth, inhuman motions of Alucard thrilled, reminded me why I loved Castlevania mythology. And the addition of Alucard’s backstory from Symphony (the only game to not star a Belmont) thrilled. I’d always been partial to Alucard’s story, that of Dracula’s son who betrays his father to save humanity.

Of course, I’ve never played Symphony of the Night, and I’ve certainly never played Dracula’s Curse. I’ve never even watched them. I know about them only in the abstract.

See, I played the original Castlevania when I was a kid and loved it. But, as I’ve said in other articles, I’m not much of a platformer. Timing, memorization: not my strong suits. I am driven more toward combination play (fighting games) or strategy and micromanagement. My natural skills lie to that direction, and nowadays I rarely deviate. But I was seven when Castlevania came out and I didn’t know my strengths. So I tried and I tried. I never beat Castlevania, never did see Dracula, but I did OK. I got to Medusa a few times. She beat my ass, though.

Instead of persisting, I tried to convince my brother to beat it. He was eleven and way more into platformers. But he didn’t really like Castlevania; it freaked him out, what with the ghouls and the monsters and the pincers. He also frustrated easily, and the Castlevanias are unforgiving games. So while he was better than I was, he wasn’t exactly “good.” And I didn’t get any satisfaction from watching him play.

But there was a kid at school who bragged about beating it. I didn’t like the kid much, but I wanted to see Castlevania beaten so I invited myself over and he played the game until the end and there was much rejoicement. Of course, I had to spend the rest of the night with the prat, but that’s really not the point.

The point was that even as an elementary school kid, I knew there were certain skills I lacked and that others possessed. I loved stories about vampires and ghosts and I liked the idea of Castlevania. But I wasn’t good enough on my own. Much like Trevor himself, I needed others on my quest. I watched someone else do what I couldn’t. It was enough.

Later, Simon’s Quest came out on the NES, and my brother and I tried that too. But it was far different from Castlevania, an open-ish world RPG-inspired nightmare of a game. It was too non-linear and confusing (and too similar to Adventure of Link, which we despised) so I doubt we gave it more than a few hours of play. This was back in ’88; the last time I played a Castlevania game was during the Reagan administration.

So how in the hell do I know Alucard’s backstory? How do I know who Trevor Belmont is? This isn’t knowledge that arrives via osmosis, like talk radio or work conversation.

In ’97, Symphony of the Night hit the PlayStation. It’s a well regarded game that is, arguably, the highlight of both the PlayStation AND the Castlevania series. Alucard steps into the role normally held for the Belmonts after Richter Belmont disappears. Gameplay is non-linear, exploration-based with RPG elements. And I’ve never played it. But Brian did and he updated me irregularly throughout ’98 and ’99. I was in another state for college, but I came home regularly enough for parties or laundry.

Each step of the way, as Brian played Symphony of the Night and mastered its intricacies, he told me the story as it unfolded. From him, I knew that Richter Belmont was (indirectly) possessed by Dracula, that the castle where the action takes place flips upside down halfway through he game and features new enemies and secrets, that it’s possible to get over 200% completion (through a glitch), and even that in the New Game + mode, one can play as Richter for a new, more difficult experience. He told me about buying weapons at the library, about the history of Alucard and Richter, about everything featuring Symphony. And he prefaced every conversation with, “If this is boring, I don’t have to tell you.”

And I’d always say, “No, I’m interested.” I used to say the same to a freshmen buddy about an X-Men spinoff series, Mutant X. We’d chat monthly and he’d update me on the newest comic. I didn’t want to read them, but I was invested enough to want to know what happened.

After Brian stopped playing Symphony is when I got interested in the mythology. And there weren’t any barriers, per se. Gamefaqs wasn’t the well-run, crazy-deep well of video game knowledge that it is today, but it more than served my purposes in 2000, when I created my account (I use the same account now). I surfed message boards and read excessively detailed FAQs on Symphony of the Night to fill in gaps, but I also dug into Simon’s Quest and Dracula’s Curse. As more games debuted, I read about them as well. I read walkthroughs and scripts to satisfy my hunger for this rich alternate world of the Belmonts and Dracula and Wallachia. I consumed just about everything easily accessible and then I moved on.

I never wrote fan fiction, but I may or may not have read a ton of it on now-defunct websites dedicated to it. I won’t say. But I will strongly imply.

After I was done reading the mythos, I moved on. I had an N64 at the time but didn’t pick up Legacy of Darkness. Nor did I feel moved to try my own hand at Symphony. I did other things, played other games. Despite my fascination with Castlevania, I didn’t want to play. I still don’t.

It’s not the games or the gameplay that entices me. I recognize that Castlevania is an exemplar of its type, of action-platform-RPG, but I don’t give a damn about the type. I don’t play Metroid anymore either, and I stopped playing Zelda games with the N64’s Ocarina of Time. But that doesn’t mean I don’t know what’s going on in those worlds. I keep up with it.

It’s sort of like when my wife, Leigh, watches those teen dramas Pretty Little Liars or One Tree Hill. I only half-watch them, but on the commercial, I have to ask, “I thought the Liars had figured out who the killer was” or “What’s up with my boy Skills?” And when she tells me, I do care. I internalize the history and the story and move on with my life.

We do this sort of exercise often. Cincinnatians who don’t give a damn about baseball, but will check in on the standings to see how the Reds are doing. Teenagers who don’t really care about their friend Missy, but want to know who she’s making out with. Readers who tapped out after Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban but scroll through Wikipedia just to see if Harry and Ron ever got their slash on. It’s the way we’re wired, curious apes who need to know what happens.

I tuned into the finale of Lost even though I’d only watched the first season. I read the synopsis for the final book in The Hunger Games trilogy. And after watching Castlevania, I pulled up the Wiki and read all about some games I’d never even heard of. Harmony of Dissonance? Rondo of Blood? I loved seeing how they all led into one another and referenced, called back. That Richter Belmont was the the main character in Rondo of Blood (badass name, that), then the ensorcelled villain in Symphony, which brought back Alucard from Dracula’s Curse? That kind of intricacy and layered mythology makes my head hurt and my heart happy.

It’s the same reason I like the Fallout series. If I’m going to not-live my life (and we can maybe agree that watching people game is to video games as masturbation is to sex), I want to not-live in a well built world. I want to feel like I’m swimming in art. Video games can be artful, and Castlevania is devoted to ensconcing the player in macabre, gothic wilderness. Watching the Netflix show felt like the fans weren’t served a platter of what they thought they wanted, but instead were given what they actually needed. It wasn’t faithful to the detriment of entertainment, but instead was a faithful interpretation, created by people who understood dedication to an ideal.

I don’t need to play Castlevania or Simon’s Quest or Symphony or Rondo of Blood, but I can sink into the water and let the surface cover me. And maybe I created a Twitch account and I’ve found some old Symphony of the Night play-throughs. I don’t know when and where I’ll have the time, but I’ll make sure to find it, because I want to see how that tale unfolded. I don’t have to participate to be part of the fun.