Still My Ancestors: A Conversation with Ashley Harris

Phil Spotswood

Ashley Harris is an Aquarius that aspires to be both a physician and poet. She attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with the Johnston Scholarship, a four-year scholarship based on merit. She graduated in 2015 with a double major in Chemistry and Hispanic Culture and Literature with a minor in Creative Writing. Her lifelong goal has been to be able to translate and create bilingual work and in May 2015 she began that journey by publishing a short story entitled “Black Wall Street” in both Spanish and English in an online magazine entitled Aguas de Pozos. After graduation, she won the Gerard Unk Fellowship Grant to travel to both London and Portobelo, Panama to study the poetry and art between the two locations. In addition, she helped Dr. Renee Alexander-Craft with her studies on the Carnaval tradition in Portobelo through the online database Digital Portobelo. She has also published her work in journals such as Event Horizon, Wusgood.black and the Yellow Chair Review. She has an upcoming poetry book called “If the hero of time was black” that will be published through Weasel Press in Spring 2018. Ashley is currently emerged in clinical research, poetry, and the legend of Zelda. Her Twitter handle is @alchemistnegra, her Instagram is @ashleyalanpoe, and her Facebook fan page is fb.me/alchemistnegra.

Ashley Harris’ poems are featured in our current issue, The Next Gen Temple Issue. I recently sat down with Ashley via Google Hangout to chat about her work with The Legend of Zelda series and her thoughts on racialized bodies in video games.

Phil: So, can you tell me a bit about your history and relationship with the Zelda series? What brought you to it? What makes it an especially complex subject for you, as opposed to similar games?

Ashley: Well that’s a great question! I was introduced to The Legend of Zelda when I was probably 12 years old by playing my little cousin’s Nintendo 64, and I remember we could never get past the Deku Tree level because there were spiders with skulls on their backs and we thought that was scary, but then one day I was provoked to finish it by my older guy cousin because he said that I was too girly to play such a game, then when I finished it I fell in love with the story, and I continued buying more Zelda games because the story of the hero coming from the woods and becoming a legend was inspiring, it’s what I’ve used to push myself in times of hardship. Also, other games don’t have the timeline, characters or rich history that each Zelda game has.

P: Yea! The Deku tree is notoriously tough, and Ocarina of Time in general – we could talk for hours about the Water Temple, I’m sure! And I like that you point out Link’s journey as a big impetus for you – there’s something so fulfilling about, as you play more of the games, sort of knowing how the timeline of that game is going to play out in general, but it’s okay because you know it’s going to be pretty weird and mystical.

A: And there is always a setback most of the time for the hero but he always redeems himself.

I think about how brave Link is, that sometimes it’s almost unreal, how many people he ends up helping because of his selfless courage.

P: That’s so true. But here is what’s weird about Link, and what you get at as a potential problem in your poems at Cartridge Lit – Link is sort of a blank slate character in that he doesn’t talk, doesn’t have a huge personality; rather, I feel we’re asked to place ourselves within his confines. But he’s somewhat of an anomaly, right? Something that you point to, that I think is especially true to the Zelda series, is that the hero is somewhat of an anomaly – the social rules of the game world don’t necessarily apply to him – he can just walk into folks’ homes without them batting an eyelash, he can smash almost everything around him and no one says anything. I think, in general, RPGs are now recognizing and interrogating this trope (of the hero/main character functioning outside the system of rules) – but I’m interested in this idea of the anomalous character, and what it allows (or doesn’t allow) for the player. It seems like the hero is supposed to be this sort of empty sprite the player can fill in with their own narrative, but as you point out, the “universality” of the blank sprite is rarely universal, and is in fact a racialized body (here: white, male, privileged with access). Is the universal character in video games a myth? Can there be anything close to a utopic game world?

A: Hmmm…

So that is hard to determine because I feel like there hasn’t been a game where the ratio of diversity is equal, for instance I can only name maybe two or three games with main characters that are brown or black. So to ask if a utopia is possible is kind of hard because most main characters have very European features and would be what would pass for privilege, like Link, who has blonde hair and blue eyes and in some cases is referred to as a benevolent hero even when he breaks into peoples’ homes and steals their money because he has this “universally appealing look.”

P: Exactly!

A: It makes sense that anyone playing a video game would want their character to look like Link’s archetype because we know in general people who look like that do in some cases have the privilege to do those actions with minimal punishment.

P: Yea. Like for me as a white male, I don’t straightaway question Link’s behavior, what I can do in the confines of his skin, because in a way I experience reality as Link. But that’s why your work is so great, I think, and why I think it’s exciting more game narrative are paying attention to these problems. How do we disassemble these built narratives? What is it about the process of poetry, specifically, of (re)contextualizing a video game and its problems through a poem, that allows for this reworking/calling out/speaking truth?

A: I think video games like pieces of art can find the Waldos that society sometimes cannot, and also, I think maybe the developers want us to think about why they do certain things in video games. I think a way to dismantle these kinds of racial stigmas in games would just be, for starters, to have a main character that is a person of color. I feel, for instance, Twilight Princess got close to doing that because it spoke about a people who were oppressed, but once again it didn’t go into much depth and you only get to go into the twilight realm once; and though Midna claims the positives of twilight, as Link you don’t really get to experience what she’s talking about. It scratches the surface because 85% percent of that game you are only seeing twilight creatures who eat people and make everything dark.

P: That’s so true; I remember being really surprised at the overall somberness of that game, sort of like Majora’s Mask, where you could maybe sense there were bigger issues just under the surface. And in TP, Link maybe gets to feel a bit of that oppression when he takes wolf form? Everyone is freaked out by this dangerous animal, right? Maybe I’m misremembering.

A: Yes! But!

Though he experiences some oppression as a wolf, I don’t know if one could say he ever experiences the joys of being a wolf. Often the experience of poc is only defined by how much we suffer and not how rich our culture is. I’m thinking about how much Midna tries to explain to him why she loves the twilight, why she doesn’t see herself as cursed but as someone who loves where she is, and loves her people. I think showing a poc main character who can enjoy the adventure and shine for who they are like Link can is just as important as showing the differences in treatment and other realities.

P: Oh, I see what you mean! I wonder if that’s a similar treatment to what Link engages in in Majora’s Mask, which your poem, “For all the masks formed”, seems in direct conversation with: he sort of takes on all these different races for his own practical/social gain, but doesn’t actually engage them wholly – they’re all sort of confined to certain functions.

A: That’s right, and it’s like, they kind of get their shine too, and they give up their powers to him…it was all such an interesting thing to think about.

P: And the speaker, at the end of this particular poem, even mentions, “I tried to be Link, / wondering / who would have to die / for me to reincarnate into / another shade”. So, in playing the game, it seems like the gamer is somewhat implicit in this violence, as the main character, going along with the mechanics and narrative of the game. At what point, do you think, is this immersion harmful/helpful/generative? Obviously we can turn the game off and refuse to play, but why do we go along?

A: Hmmm…

Well it’s interesting, because as you said Link is like a blank slate…sometimes I feel that way with white culture, there are standard nationalistic things that define whiteness, but also a big part of what makes whiteness what it is, is how it can dominate others or make others inferior, and also how well it can take from others, this freedom of swapping bodies without worry, without fear. I think the immersion was great for Majora’s Mask but at the same time it was creepy because those main characters couldn’t be with you. You had to be them, for them.

P: Yea, definitely, the whole game is pretty messed up.

A: It can be but I also think it’s truly…somber. I think some themes of death are addressed well; but some things, like how Deku scrubs are treated or how they look is disturbingly offensive.

P: Earlier you mentioned some video games that center poc characters; what video games have you played / are interested in that directly or indirectly address these problems or silences of racialized bodies in built narratives?

A: One game I know…doesn’t center poc per say, but instead it centers a marginalized group of people–they’re half elves and they’re oppressed because of who they are, constantly murdered and enslaved–that was Tales of Symphonia. As for others, my friends would know – which is sad – I want to know more!

P: Oh, that sounds good; reminds me of the blood mages and Qunari in the Dragon Age games – are you familiar with that series?

A: I’ve heard of them but I don’t think I’ve had the chance to play them yet! But yes, it was a good game – it was deeeeep and looonngg.

But what would a black hero look like? That’s why I wrote my book.

P: Those are some of the best! And yes! That was my last question! In your bio you mention you’re working on an upcoming poetry book, if the hero of time was black (Weasel Press 2018) (which I’m so excited about, inherently) – can you talk a bit about the book? Does it expand on any of the themes and problems you bring up in these poems?

A: Sure! It does!

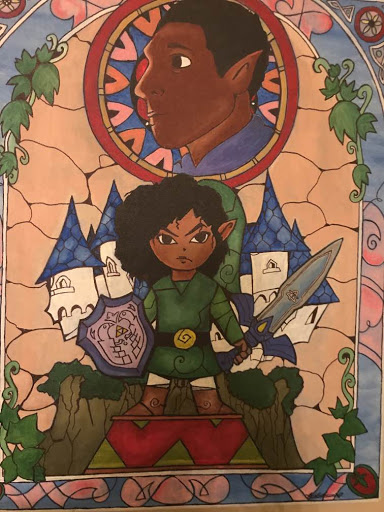

So when I first started this book I referred to my favorite game in the series, Wind Waker. In fact, here’s a picture of the cover:

P: Wowowowow, that’s incredible!

A: Yes! I liked that Link the best because he wasn’t related to the hero of time but folks still considered him to be his ancestor. I think about all the black leaders before me and how we aren’t related by blood but how they are still my ancestors and they still loved me. Instead of Zelda in the background, I put Stokely Carmichael, and thanks! I had my friend paint it!

But anyways, I tried to go down different timelines in the series from there and envision the experience of a black hero.

P: That sounds so rich; and with the Zelda series, there really are so many timelines to explore; which is another cool thing about the series, its narrative is both there and somewhat vague, open to interpretation – it’s malleable.

A: Yes!!! I had an open field.