High Scores: Kraid’s Lair

James Davis

What makes videogame music distinct as a genre? How does it differ from the music that accompanies, say, a cartoon, or a movie, or a ballet?

One major distinction is constraint. Videogame music was born into considerable limitations—the three sound channels of the Atari 2600 or the comparatively luxurious five of the NES: two for pulse waves (usually used for melody), one for triangle waves (usually for bass), one for noise (almost always for percussion), and one for extremely primitive samples (used rarely). There’s something inherently poetic about these constraints, and I’m constantly impressed by how NES composers managed to create such rich texts within such claustrophobic confines.

In the decades since the NES, despite the leaps forward in audio technology, the spirit of the resourceful early compositions is still very much alive. Chiptune composers deliberately recreate the NES’s limitations not only to evoke the sound quality of the genre’s foundational texts but also to produce the creative problem-solving that composers like Hirokazu “Chip” Tanaka had to use when composing for early titles like Kid Icarus and Metroid.

Another distinguishing characteristic of videogame music is the importance of melody, which matters in film soundtracks, too—as leitmotif and tone-setting—but in video games, as in ballet, melodies are the only audible voice. They have to express everything: the environment, the characters, the plot. Aside from those primitive samples, the human voice couldn’t do any of the emotional heavy-lifting. Simple but memorable melodies allowed these early songs to withstand looping while telling the player where they are and how they should feel.

Metroid is a particularly interesting soundtrack because of how it resists melody. In a sci-fi horror game, a catchy melody might sound too comfortable. The deeper into Metroid you go, the less melody characterizes the soundtrack. You start off in “Brinstar” with its intrepid, galloping tune. You progress to “Norfair,” where the theme is dark, heavily interrupted, but still legible. Past Norfair, you arrive at “Ridley’s Lair,” where the melody, such as it is, consists of four notes that alternate keys and repeat ad nauseam. It’s an incredibly frustrating, trollish area in the game, and the music makes you want to get out as quickly as possible.

The game’s best song, “Kraid’s Lair” (a.k.a. “Kraid’s Hideout” or “Brinstar Depths”), is both dark and richly melodic. Like “Brinstar,” it consists of a few phrases that build to a sort of climax. But the number and complexity of these phrases in “Kraid’s Lair” are greater than in its happier upstairs neighbor.

“Kraid’s Lair” consists of five repeating phrases.

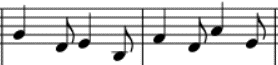

The first has two measures, each of which alternates between quarter and eighth notes and ends on an accidental. This slow, uneven rhythm, combined with the accidentals as transitions, creates an air of mystery and danger. The phrase is repeated four times and takes up eight of the loop’s 28 measures. Tanaka lets us marinate in the unease of this opening phrase before developing the theme further.

The second phrase complicates things by going lighter. The uneven rhythm repeats, but the melody brightens since all the phrase’s notes are natural to the key. Of course, Tanaka doesn’t let us enjoy this respite very long. While the first phrase repeats four times, the second phrase only plays twice, just long enough to lull us into a false sense of security.

The third phrase attacks that security by doubling the rhythm and piling on accidentals. We go from four notes per measure to twelve, quickening the pace just as Samus’s heart might speed up as she tries to escape a pit of acid. Almost half the notes are flat or sharp. This volta is extremely unsettling and exciting.

The fourth phrase of the melody is in some ways predictable and in other ways a complete surprise. Just as the second phrase naturalizes the “off” eighth-notes in the first phrase, the fourth phrase smooths out the accidentals of the third. This fourth phrase is surprisingly beautiful and poignant, not only because of its friendlier notes but also because of its range, about one-and-a-half octaves, including the highest note in the whole song, two A’s above middle C. There’s also just the slightest break in the melody at the end of this phrase, a sixteenth-rest to let us catch our breath. This phrase is the song’s climax, and the tiny rest sets off the sense of importance.

The fifth and final phrase is the song’s shortest: one measure as opposed every other phrase’s two. It’s also the most rhythmically and melodically simple, beating out the same six eighth-notes four times, starting with the high A from in the previous phrase: A, G, F#, E, F#, G. After the emotional roller coaster of the previous four phrases, this denouement gives us a few seconds to check our pulse and prepare for the unease that the first phrase will reintroduce.

Every note in this melody’s five phrases feels purposeful. The bass is simple enough to let the melody speak for itself. “Kraid’s Lair” does not take advantage of the NES’s noise channel, imposing limitation upon limitation. The lack of percussion makes the song quiet, haunting in a way that the Morse-code-like dits and dahs in “Brinstar” and “Norfair” would ruin. In addition to the fear, anticipation, and wonder the melody evokes, it also feels lonely, which is appropriate to the game and its inspiration.

A number of Nintendo’s main franchises have roots in horror films. We get Mario via Donkey Kong, which is of course via King Kong. And we get Metroid via Alien: the boss Ridley is a nod to Ridley Scott; Mother Brain is analogous to Mother, the Nostromo’s onboard computer; the parallels between Samus and Sigourney Weaver’s Ellen Ripley are not negligible. However, Tanaka has stated in an interview that the music of Metroid was not directly inspired by Jerry Goldsmith’s score for the 1979 film. Rather, Tanaka took inspiration from the film’s overall emotion, its “urgency, tension, and uneasiness.” This makes sense to me: Goldsmith’s score is avant-garde, ambient, dissonant, bleak. The Metroid score has these qualities in moments, but it’s far more classical, especially in “Kraid’s Lair.” While the Alien soundtrack resists themes, the Metroid soundtrack is full of them. “Kraid’s Lair” is often mistitled “Kraid’s Theme.”

The closest analog I can think of to “Kraid’s Lair” outside the world of video games would be Mark Snow’s “Materia Primoris,” the famous opening theme of X-Files. Both are ambient but melody-driven, dark but catchy. They bear relistening. Even Angelo Badalamenti’s “Twin Peaks Theme” has qualities that would not be out of place in Metroid or another nonlinear, Metroidvania-style platformer. Television theme songs have to make the most of a minute or so, establishing tone and capturing the audience’s attention. Their melodies need a beginning and end, but they also need to be repeatable. In this way, they are a helpful parallel in considering how videogame music works as a genre.

Then again, a TV theme’s repetitions are not nearly as immediate as those in a videogame theme. And TV themes only tend to play at the beginning and end of an episode. Video games play themes throughout—there is a density and forwardness of melody in video games that is more akin to opera or ballet than film or television.

Ultimately, I think the difficulty of finding a perfect analog for videogame music in the “real world” is a good thing. It speaks to the distinctness of the genre, its unique expressive capabilities. As videogame technology continues to enable more and more sonic sophistication, composers will do well to remember that constraint, repetition, and melody are inherent to the genre’s uniqueness.